We Need a Movement

Author: Sheri Denkensohn-Trott

If you have not done so already, you should watch the documentary Crip Camp. It shows the stark contrast with the accessibility of today’s world with the world of those with disabilities in the early 1970s. Individuals with all types of disabilities finding pure joy by getting out of the city, even though they had to travel in the back of a truck or be carried onto a bus to get to camp. For many it was utopia. A place to  be free from the constraints of others and the ability to be treated as human beings with thoughts and desires. I watched with tears running down my face, feeling almost guilty for my “luxuries” in life as a woman with a disability. I am a quadriplegic injured in 1983. Things were far from perfect, but my parents would never contemplate that I should be kept home from school. I missed my entire junior year of high school, but teachers from my school in the small town where I grew up came and tutored me for free in the summer and I was able to go back senior year and graduate with my class.

be free from the constraints of others and the ability to be treated as human beings with thoughts and desires. I watched with tears running down my face, feeling almost guilty for my “luxuries” in life as a woman with a disability. I am a quadriplegic injured in 1983. Things were far from perfect, but my parents would never contemplate that I should be kept home from school. I missed my entire junior year of high school, but teachers from my school in the small town where I grew up came and tutored me for free in the summer and I was able to go back senior year and graduate with my class.

I was still wrapping my head around what happened to me. I had never met a quadriplegic and my community did not have sidewalks or curb cuts, so I was a prisoner in our driveway unless we went somewhere in my big Ford Econoline van that had a lift. I did go away to college, largely because of the great vocational rehabilitation counselor that was assigned to my case. He had connections at the University at Albany, Office of Disabled Student Services. My family took me up to Albany on a weekend and I upon arrival I could envision a world of possibility. I met a woman named Sheila who looked just like me as a quadriplegic in her motorized wheelchair, and she was living on campus and successfully navigating college life. It was 1985, five years before the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA). But a law called the Rehabilitation Act of 1978, required  that entities like state colleges, have programs and activities accessible to individuals with disabilities. The statute was not clear as to what “accessible” meant.

that entities like state colleges, have programs and activities accessible to individuals with disabilities. The statute was not clear as to what “accessible” meant.

I moved to college and had my own dorm room in a suite with four other women. At that time there wasn’t any social media, so I had to decide whether I would tell my roommates over the phone about my disability (they gave us the phone numbers and names) or whether I would wait until I met them in person. I decided to wait, because I was scared that they would conjure up some view of me in their minds that would be like a twisted creature in a horror show. It turned out that they were fully accepting of my disability and wound up helping me with meals and other tasks. I did have personal attendants and that was not easy. It was hard to find reliable people and many qualified people did not want to work on a college campus. But I survived. Sometimes I wonder how. Memories of huge snowstorms and trying to get to class, buses to get from place to place without lifts, and large lecture centers with nowhere to sit but way up on the top where I could hardly hear the professor. Those are just a few of the accessibility challenges that I faced.

I went on to law school after graduating college and moved to Washington DC, where it was more accessible. I do not drive, so being in the DC area gave me the ability to maximize my independence because I could use the Metro, buses, and wheelchair accessible taxis. Access wasn’t perfect, but thinking back to Crip Camp, I was able to get around independently and live in a community where there were other people with disabilities.

I was in law school when the ADA passed, and I soon learned about its many provisions and requirements. I also saw firsthand the significant pushback from the business community. I was privy to conversations with comments such as, “Why do we need to spend money for “these people?” They just sit home and collect benefits anyway.” I couldn’t believe that along with physical obstacles, that there were so many attitudinal barriers.

Things have certainly improved in the 30 years since the ADA was passed and since the days of advocacy that grew out of Crip Camp. I so admire the individuals that had the tenacity and endurance to spend  days doing sit ins in the West Coast office of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (the precursor to the US Department of Health and Human Services). This same group of activists stopped traffic in the middle of NYC, and eventually came to Washington DC and climbed up the steps of the Capitol on their hands and knees. Those individuals fought with their lives for the civil rights that we have today.

days doing sit ins in the West Coast office of the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (the precursor to the US Department of Health and Human Services). This same group of activists stopped traffic in the middle of NYC, and eventually came to Washington DC and climbed up the steps of the Capitol on their hands and knees. Those individuals fought with their lives for the civil rights that we have today.

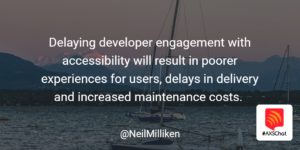

That is why I am so adamant that we continue the fight. Most of the individuals who fought for regulations implementing the Rehabilitation Act, leading to the passage of the ADA years later, are no longer with us. Yes, access is much improved and attitudinal barriers are diminished to some extent. But there are still entities that are built with steps that are not needed, counters that are too high, hotels that are barely accessible even though they claim they are, and technology like telemedicine and other virtual platforms that are not fully accessible.

We have seen what our predecessors went through to get to where we are. It is our moral obligation to ensure that the ADA stays strong and that the tweaks that are needed to fit the environment that we live in today are made. We cannot afford to have our civil rights eroded or ignored. Universal design is good for everyone. And every single individual with a disability has a right to an education, employment, and housing in a community. These are basic rights that cannot be forgotten, regardless of the tight budgets within counties, states, and the nation.

Let’s celebrate what we have achieved over 30 years. At the same time, we cannot forget those who gave their lives to get us to where we are today. We need to continue the fight. We are a community. Let’s rise up, use our voices, and make sure that the ADA is followed going forward and that accessibility for all is embedded in the minds and hearts of our leaders.

Let’s celebrate what we have achieved over 30 years. At the same time, we cannot forget those who gave their lives to get us to where we are today. We need to continue the fight. We are a community. Let’s rise up, use our voices, and make sure that the ADA is followed going forward and that accessibility for all is embedded in the minds and hearts of our leaders.

wheelchair part-time for about 5 years. So, the true importance of accessibility was not really something I was, personally, worried about for myself. Of course, things are quite different now and I am extremely aware of accessibility issues (and, of course, issues of inaccessibility). I have been a full-time wheelchair user for about 17 years and unless there is a miracle, I will be for the rest of my life. To me the ADA means access of all kinds; physical, emotional, psychological, et al.

wheelchair part-time for about 5 years. So, the true importance of accessibility was not really something I was, personally, worried about for myself. Of course, things are quite different now and I am extremely aware of accessibility issues (and, of course, issues of inaccessibility). I have been a full-time wheelchair user for about 17 years and unless there is a miracle, I will be for the rest of my life. To me the ADA means access of all kinds; physical, emotional, psychological, et al. be added to the previous sentence: who know how to apply it.

be added to the previous sentence: who know how to apply it. build counters that are inaccessible? Why do hotels say they have roll in showers when they don’t? Why do stores say that they are accessible and upon arrival there is one step? Understanding what is required from a range of individuals is necessary to fully realize the benefits of the ADA. If I had my way, every architect, doctor, developer, and store owner, among others, would receive a crash course on what is required under the ADA. It is only then that we will reach systemic accessibility because it will be applied correctly from the start.

build counters that are inaccessible? Why do hotels say they have roll in showers when they don’t? Why do stores say that they are accessible and upon arrival there is one step? Understanding what is required from a range of individuals is necessary to fully realize the benefits of the ADA. If I had my way, every architect, doctor, developer, and store owner, among others, would receive a crash course on what is required under the ADA. It is only then that we will reach systemic accessibility because it will be applied correctly from the start.